Masterpiece Online 2021

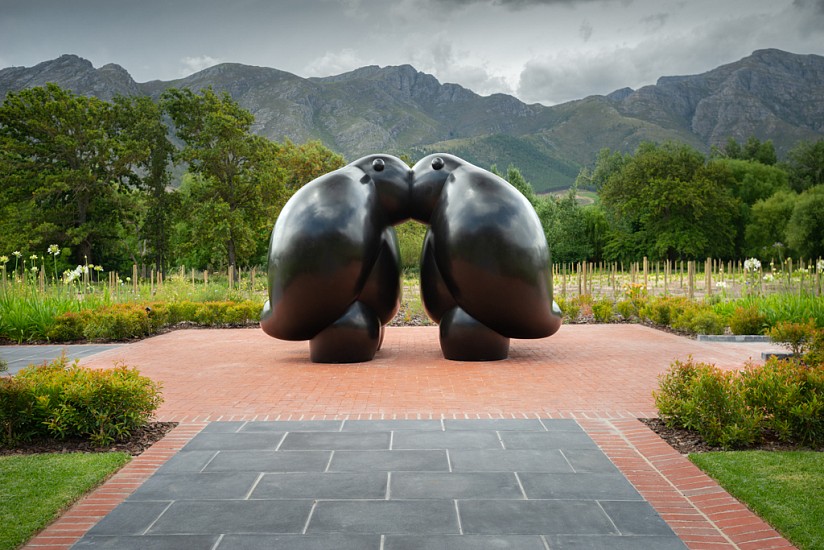

Almost certainly the most iconic of Sanell Aggenbach’s work of the last few years is Madre Pietà, Aggenbach’s distinctive re-interpretation of Michelangelo’s marble sculpture. The original is a seminal Renaissance masterpiece, merging classical ideas of beauty, naturalism, youth and maternal affection. Instantly recognisable, it is also the only artwork which Michelangelo ever signed.

Aggenbach’s take is witty and slightly ironic, reimagining the two figures as stuffed rabbits gleaned from her children’s toy box. While there is a comical pop art element to the rabbits’ rounded extremities, the sculpture is also … touching and sympathetic. Aggenbach deftly contrasts a rigid medium saturated with masculine connotations (bronze) with plush figures that are fundamentally feminine and nurturing, accentuating the ideas of maternalism and youth in Michelangelo’s original.

- Tim Leibbrandt

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Photo credit: Michael Hall

‘I don’t know if I summoned these figures, or they summoned me to make them. They just developed this enormous presence and I started thinking about the notion of the gods in Western society and how we view them as either myth or fantasy or new age. For me, these five figures are absolutely benevolent. I view them as forefathers. I believe that we are all gods, we have just forgotten, and we are stuck down here repeating old patterns and habitual addictions. The Ancient Ones are memories of what we were.’

‘I am often asked about the small figures emerging from the crown of their heads. I have begun to realise that for me they represent the revealing of the spiritual self. The fact that these sculptures have fully realised figures with whole bodies shows that they are spiritually evolved beings. The men have female figures on their heads and the women have male figures on their heads. So, they also represent a marriage of the masculine and feminine and an owning of the full self, the complete self.’

‘It took me years to realise that I was interested in art that can change the world. That intent and creation can alter one’s reality. And I believe that is what art was used for in many cultures. We just don’t see it that way in contemporary Western culture. For me, every single artwork is more of a spiritual discipline about inner transformation. My work is about spiritual transformation. I like to believe that other people will feel that as well. I cannot force it, but if it happens for me then I like to believe that it can happen for others too.’

- Deborah Bell, Interview with Tim Leibbrandt, Artthrob, 2016

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Photo credit: Michael Hall / Dan Weill Photography

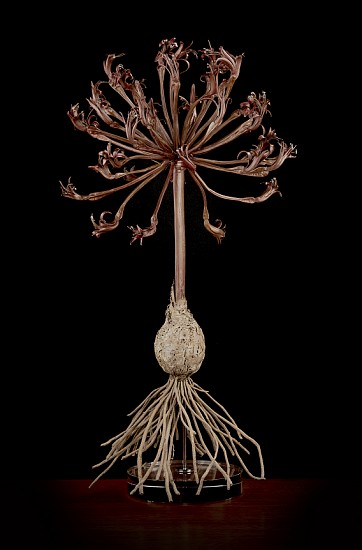

Regarded as one of the world’s finest botanical sculptors working today, Nic Bladen makes his home in the ecological jewel that is the southern tip of Africa. Through the alchemical process that transpires in his studio’s furnaces, the artist creates delicate artistic reconstructions of astoundingly beautiful flowering plants. The precision and care required to cast and reconstruct lifelike replicas is immense, and Bladen has become a master of his craft.

Central to Bladen’s mission is a desire to preserve the singular beauty of plants through his art, and with this unique bronze cast of Brunsvigia orientalis, the artist shines a light on the extraordinary form and beauty of the ‘chandelier lily,’ indigenous to the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Image credit: David Junor / Artist portrait: Etched Space

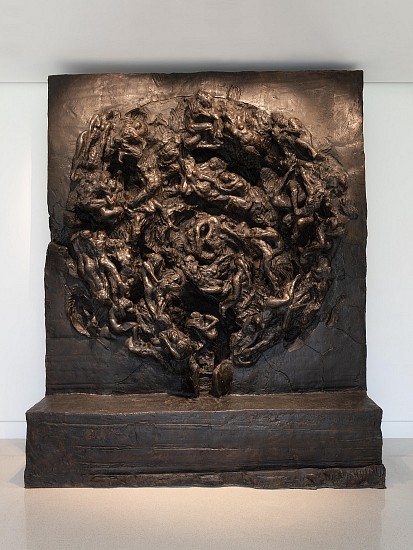

The initial manifestation of Dylan Lewis’s Chthonios – a striking image of a maelstrom of forms – emerged following a six-year period of intense self-discovery. Perfectly encompassing the themes of self-actualisation, struggles within human relationships, and striving for liberation from harmful internalised indoctrination, the work concretises the turbulence of human emotions.

During lockdown in 2019, Lewis set to work on producing a monumental incarnation of an earlier work, allowing it to evolve intuitively and organically rather than through exact reproduction. The result is a visceral large-scale sculptural work which recalls Rodin’s magnum opus The Gates of Hell and William Blake’s The Lovers’ Whirlwind. Both of these saw the artists drawing on the evocative imagery of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, but vehemently eschewing any moralising allegory in favour of celebrating the full spectrum of the human experience in all its complexity. With Chthonios, Lewis extends this striking, chaotic imagery to reflect on the agony and ecstasy of trying to connect with the ‘other’ – both other human beings and with the self.

Chthonios marks a significant culmination in the narratives that have underpinned Lewis’s work from the very beginning: the searching for wholeness and self-actualisation against forced familial, cultural, and social conformity. Lewis captures the sense of the sublime that comes from standing on a precipice and witnessing the tumult. It is a view from the eye of a storm, a reckoning with the prospect of being pummelled by a chaotic maelstrom of human emotions and being unsure of whether it will utterly destroy or bring about the intense desire for wholeness.

The sculpture takes the form of large circular arrangement enclosed within a square. This contrasting of the two shapes recurs throughout a diverse array of mandala traditions in a number of world religions, throughout alchemical symbolism, and even in Jungian analytical psychology. Common throughout these various incarnations is the idea of a circle within a square as a symbol of wholeness or totality, contrasting boundlessness with lucidity. This is exactly what Chthonios represents for Dylan Lewis.

- Adapted from an original text by Tim Leibbrandt

Photo credit: Michael Hall / Artist Portrait: Stella Olivier

Widely regarded as the leading figure in the realist movement in southern Africa, John Meyer’s love of paint is at the heart of his enduring prominence as an artist. The magical properties of paint and his ability to conjure nuance with it – the way the light falls on a landscape and the branches of a singular baobab tree, illuminating and spotlighting our mysterious world – is at the heart of his preoccupation with painting. This has haunted, inspired, and propelled him as an artist for nearly 50 years.

While Meyer’s concerns appear to be about presenting reality, it is his preoccupation with manifesting his imagination as reality, that has won out. Many of his landscapes do not exist, however intimately we feel we know them. This is his genius. They present his and our memory of landscape, and how it feels – or might feel – to be in these places.

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Photo credit: Michael Hall

The Fundamentalists by acclaimed South African artist, Brett Murray, were created as part of a recent body of work entitled Again Again and continues the artist’s abiding preoccupation with our tendency to perpetuate past mistakes and repeat the cycle again. And again.

Murray’s monumental gorillas butt heads, seemingly locked in an eternal impasse. The artist ‘darkly ponders the fatal turn in every conversation that reduces conflict to its extremes … thereby killing the very heart of debate. If no one can speak each to each then what is left but a crazed blather full of sound and fury, signifying nothing? It is this nullification, this dead-end, which for Murray sums up the times.’*

‘I think we live in interesting times,’ says Murray, ‘where conversations are becoming more and more polarised and the rights and the wrongs of your political positions are becoming more difficult to define, and there’s a big grey area in the middle. Often what an artist can do is prick holes in that divide and I think some of my work does sometimes do that – and it’s potentially uncomfortable. I continue to feel the urge to expose the absurdities of the powerful through satire. Through my work I hope to explore my jaundiced love/hate relationship with South Africa’s unfolding democracy.’

* Ashraf Jamal, writer and cultural theorist

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Image Credit: Michael Hall / Artist portrait: Stephanie Veldman

‘Borrowing from the language of Surrealism, the anarchy of Dada and the figurative violence of Neo-Expressionism, particularly the work of American artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ngobeni’s paintings are characterized by obsessive mark making and littered with overt political references.’*

Blessing Ngobeni’s large canvases incorporate a range of cuttings, discarded materials and found objects. These unassuming materials are layered to create textured and powerful works which often reference artists who have influenced Ngobeni, both conceptually and aesthetically.

Having used his art to fearlessly critique the structures of power, overtly addressing the corruption, hypocrisy and greed of the contemporary ruling elite, this new triptych strikes a more jubilant note, the figures process exuberantly across the canvas, their dancing skirts in luminous shades of pink, red, blue and yellow.

* Vitamin P3 New Perspectives in Painting, Phaidon, 2016

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Artist Portrait: Courtesy of Standard Bank

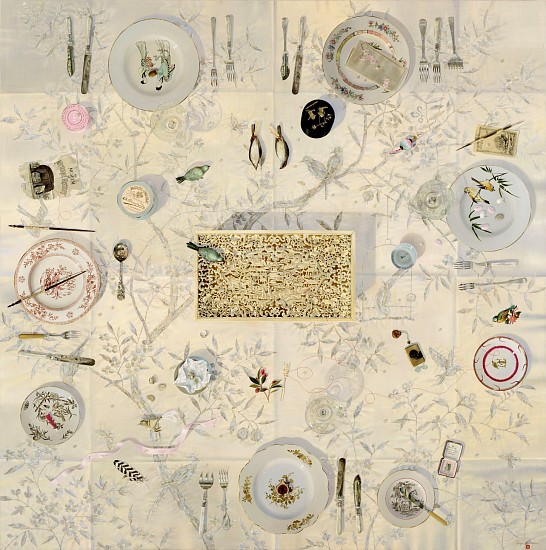

Caryn Scrimgeour’s paintings are obsessively immaculate – a manifestation of intense attention to detail and an extraordinary command of her palette. Her table settings intrigue and fascinate by juxtaposing fragile and precious curios with commonplace objects, each exquisitely rendered. Rich in symbolism, her work is reminiscent of still life paintings from the Dutch Golden Age. She uses ephemeral objects – blossoms, birds’ eggs and glistening fruit – to remind us of our fleeting existence.

Scrimgeour’s paintings are puzzles, much like our identities, made up of fragments freighted with memories and experience. They are vanitas paintings for our age, hinting at the fragility and transitory nature of our lives. Similarly, the fragments recorded are small monuments to the human desire to leave what Antony Gormley describes as ‘a trace of our living and dying on the face of an indifferent universe.’*

* Antony Gormley, interview with the Financial Times, 2015

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Photo credit: Michael Hall

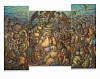

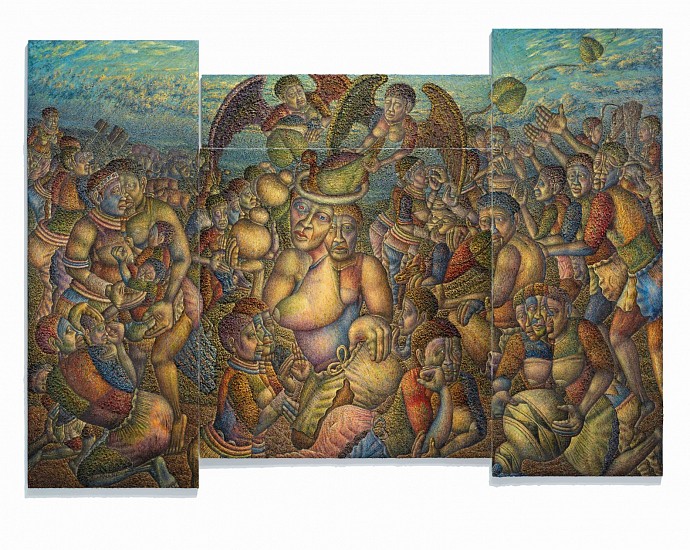

Who Are We and Where Are We Going? is undoubtably Mmakgabo Sebidi’s magnum opus, created over four years, at the height of her creative powers. An epic and endlessly enigmatic work, Sebidi invokes and reinvigorates Renaissance mainsprings like the Adoration of the Magi, and other canonical works. Here though, Mother Africa, rather than the Madonna and Christ, holds court in a mythical Valley of a Thousand Hills, an otherworld that recalls another South African masterpiece – the controversial, fantastical, and numinous Indaba My Children by Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa, variously considered the bible of African folklore.

Aptly, as the matriarch of contemporary South African art, 10 years after the advent of democracy, Sebidi titled this distillation of her visions and dreams, hopes and fears with a question, a foundational provocation that lies universally at the heart not only of artmaking, but also of philosophy, spirituality and life itself.

Interestingly when read as allegory, one might see a panoply of abundance and one senses that Sebidi is urging us to seek the answer in a return to essence, to traditional values, all the while exhorting us to imagine a fantastically fecund future, steeped in inherited, ancestral wisdom and humanity. When read as a mirror of our current existence Sebidi’s polyptych makes no attempt to answer the question. The painting is the question. Fraught with the confusion, schizophrenia, and cacophony of the ‘post-everything’ world, there is something of the bitter-sweet – a snapshot of the soul of a people both beleaguered and ascendent; of a dawn and a dusk; of a knowing and an unfathomability – an African Renaissance both nascent and tumultuously ancient.

Contact: info@everardlondon.com

Photo credit: Michael Hall